Attention Is Ball You Need

How the architectural foundation for AI language models can be applied to BasketWorld

I posted the above Note a little while back about a curiosity I had found in my BasketWorld models. Basically, the issue I was running up against was that the model was learning “quirks” related to how agents were being indexed (or ordered or “slotted”) in the input or observation space. To illustrate, imagine we have just two features in our input space: 1) normalized player coordinates and 2) a one-hot encoding (OHE) for the index of the agent that currently has possession of the ball. Here’s a numerical example of what the observation might look like for one step of a 3-on-3 matchup:

[0.1250, 0.5000, 0.2500, 0.3750, 0.1250, 0.6250, 0.1250, 0.4375, 0.0000, 0.5625, -0.0625, 0.5000, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0]

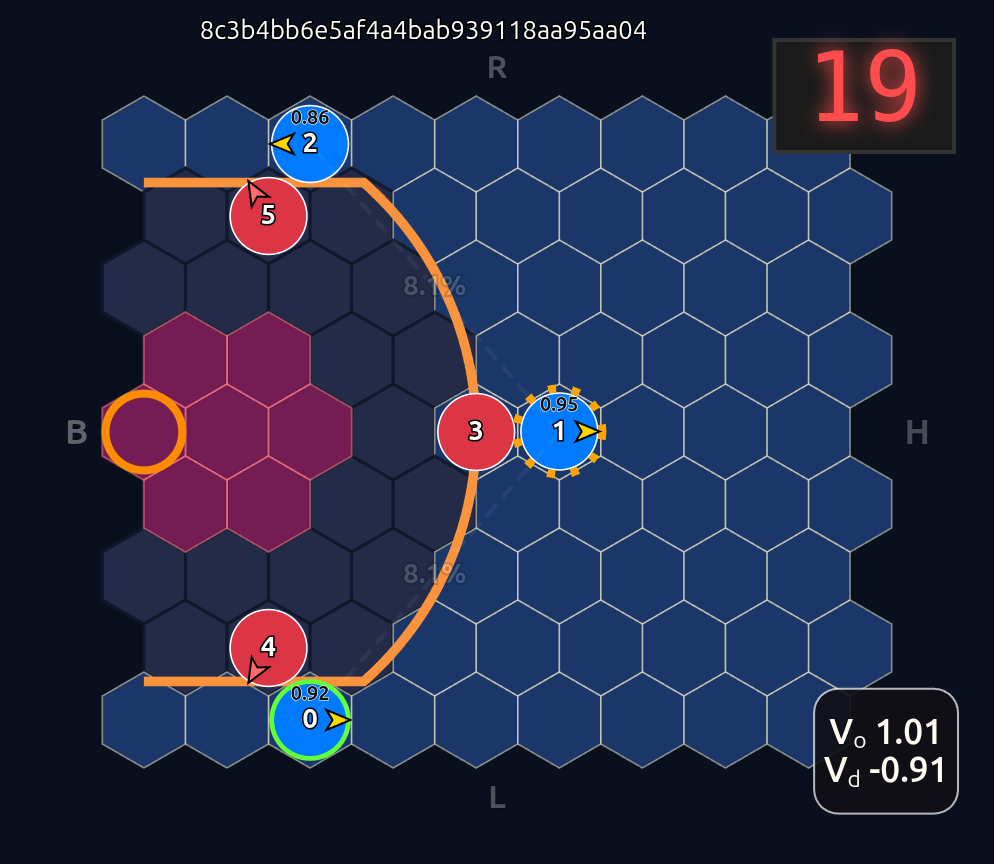

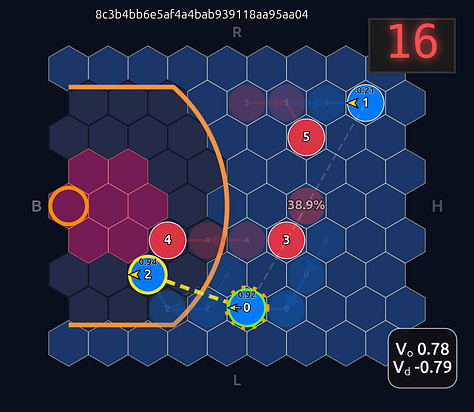

This is an 18-dimensional vector where the first 12 dimensions encode the normalized axial (q, r) coordinates for each player and the last 6 dimensions are the OHE for the ball handler. In this example, the offensive agent “#2” or O2 (zero-indexed) has the ball. This encoding seems harmless enough, but consider that there is a neural network (NN) behind the scenes that is trying to learn the importance or weight of each feature. In this architecture each “slot” in the input space is given some weight that is learned during a training run. The problem that arises is that the model will inevitably violate an implicit physical assumption I had in mind which is positional invariance (not to be confused with “positionless basketball”!). In plain language it shouldn’t matter which agent or id is in which “slot”. The model shouldn’t care whether “Agent 2” or “Agent 1” has the ball if they are in the exact same position on the court and the game state is otherwise exactly the same. This was the “experiment” I was performing in the Substack Note above. I noticed that if I swapped positions of the agents I got significantly different policy probabilities ceteris paribus —even if everything else was held constant (coordinates, shooting skills, etc). The model was violating positional invariance. You can see this in the screenshots here where I’ve swapped players keeping everything else the same:

So how to solve this? The first line of attack I chose was to employ various kinds of intentional permutation of slots during training with the idea that this would prevent the model from learning slot-specific weights. Alas, while it did mitigate the problem somewhat it didn’t fully resolve the issue.

The real solution turned out to be using the concept of attention and specifically, transforming the input space into position invariant tokens. (Highly recommend reading the original Attention Is All You Need paper and for even more pedagogical delight this well known blog post.) This is actually a pretty neat trick because it starts to look and feel a lot more like a large language model. It also expands our ability to create more interpretable models as you’ll see later in the post. So let’s take the earlier 18-dimensional example and transform it to the attention-based token space:

[0.1250, 0.5000, 0.2500, 0.3750, 0.1250, 0.6250, 0.1250, 0.4375, 0.0000, 0.5625, -0.0625, 0.5000, 0, 0, 1, 0, 0, 0]

becomes →

[[0.1250, 0.5000, 0], [0.2500, 0.3750, 0], [0.1250, 0.6250, 1], [0.1250, 0.4375, 0], [0.0000, 0.5625, 0], [-0.0625, 0.5000, 1]]

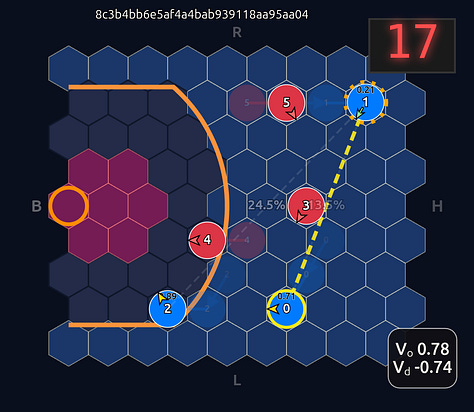

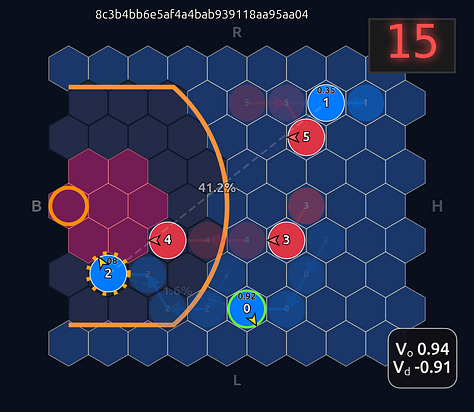

Voila! Now instead of an 18-dimensional vector we have six 3-dimensional vectors or input tokens. And going further we employ a shared network trunk that has to use the same weights for each slot inside each token. So the order of the tokens is made irrelevant and more importantly unlearnable. The model can only learn weights that are related to the internal token features. So as long as those features are not tied somehow to position id, we should have complete positional invariance as demonstrated below when we now swap players 1 & 2:

Note how the action probabilities for each agent and value function (lower right) is identical before and after the swap of positions. This is because aside from swapping their ids, the game state is unchanged otherwise.

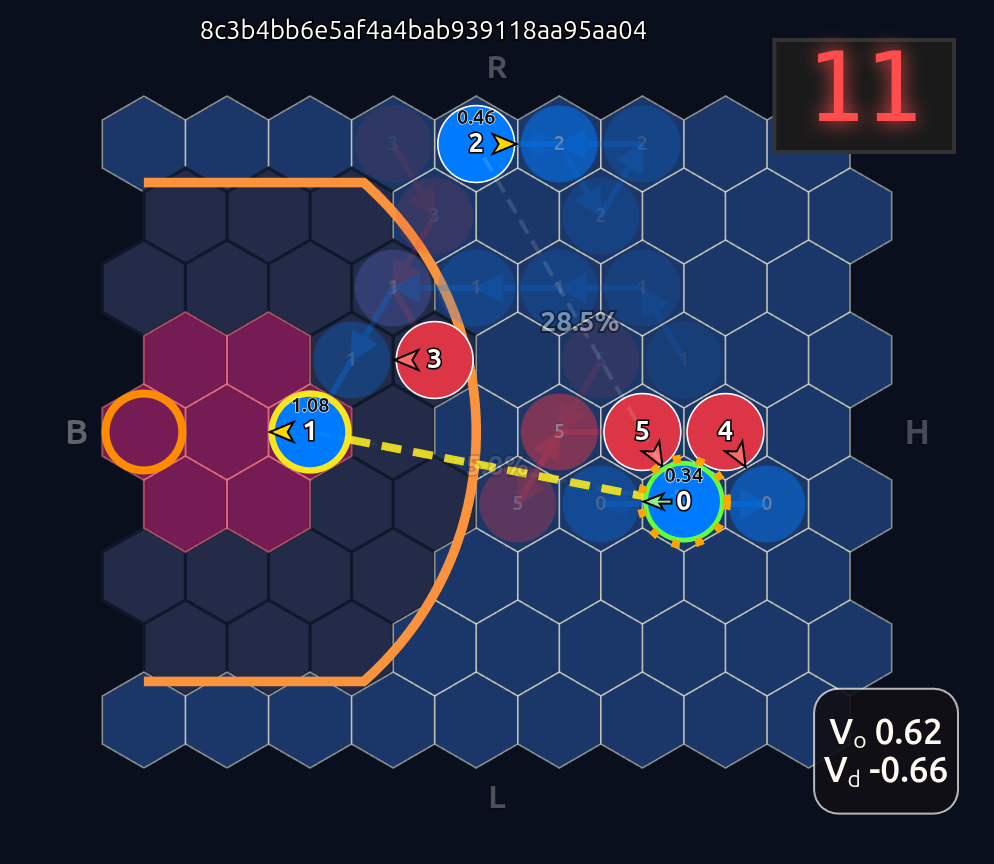

With this simple twist we can now also employ multiple attention heads to learn different higher level BasketWorld features. In the very literal sense of the word, the idea here is that the model learns to pay attention to game states such as “who has the ball”, “who is the nearest defender to me”, “how much time is left on the shot clock?”, via self-attention and cross-attention. You might be wondering at this point how it can learn all that based on the example observations above where we just had position and ball-handler encoding, but of course, our actual BW environment has a lot more state detail. Here is a real instance of a game statet taken from an episode of game play:

Token View (Set-Observation)

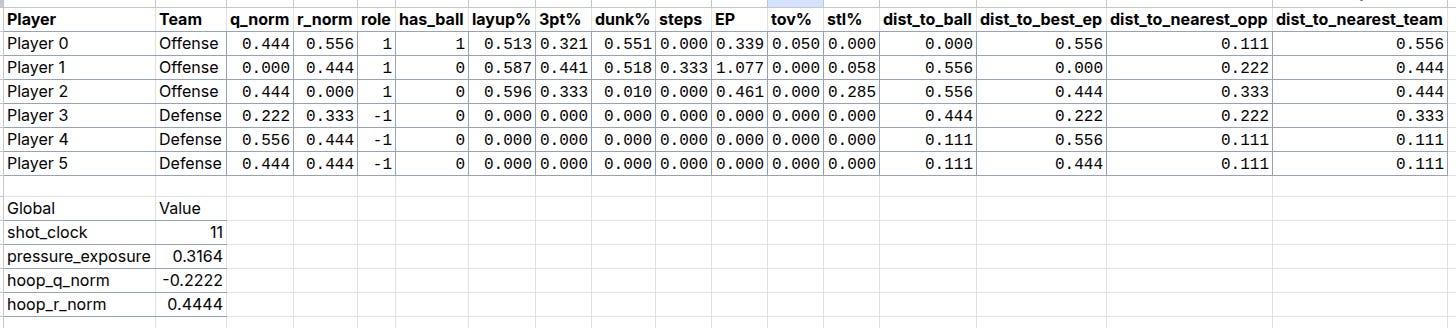

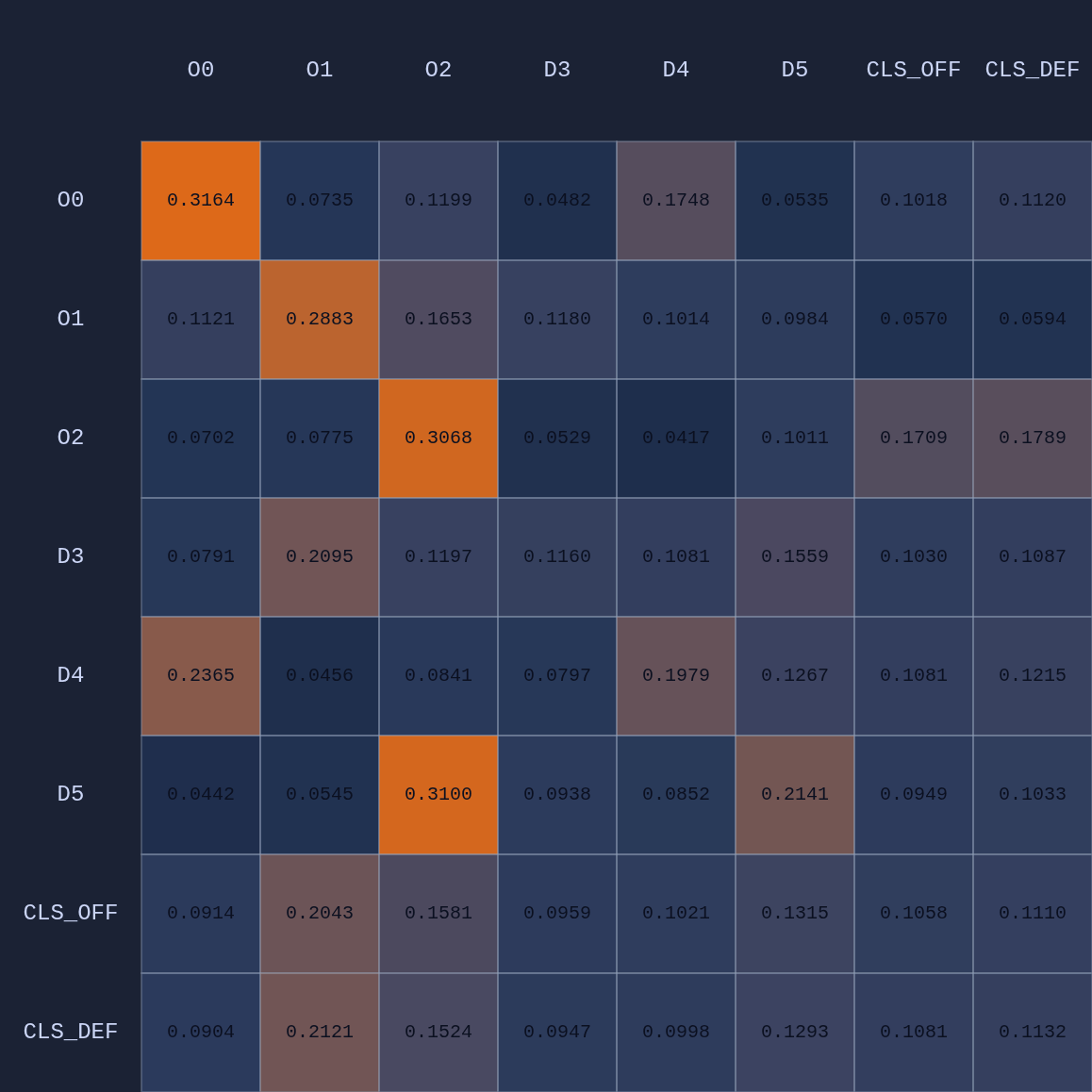

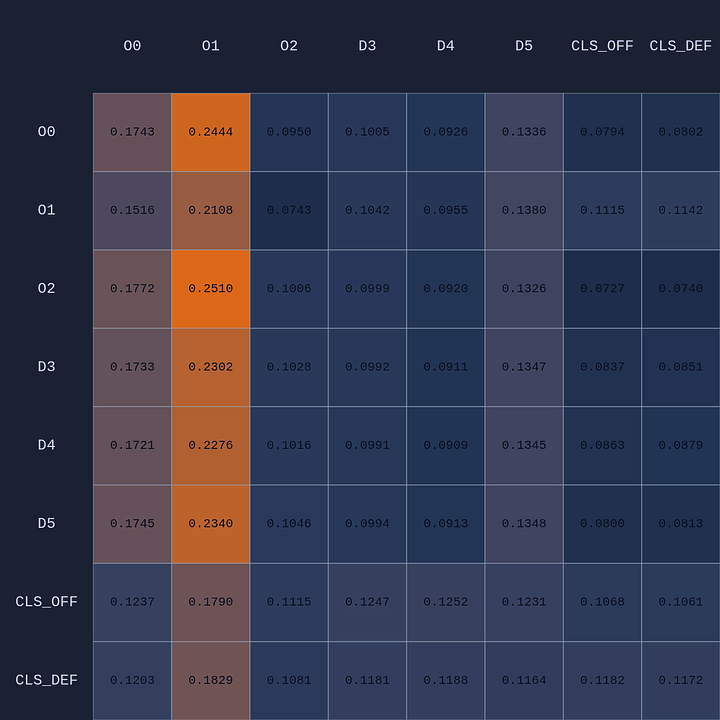

So in this example we have 6 input or observation tokens, and each token has 19 dimensions, 15 of which encode “self-features” and 4 global features that are appended to the player tokens. These inputs are routed through the shared MLP of the neural network into learned embeddings which then go through our attention module and some other layers before the final layer. We can visualize an Attention Map given any arbitrary game state:

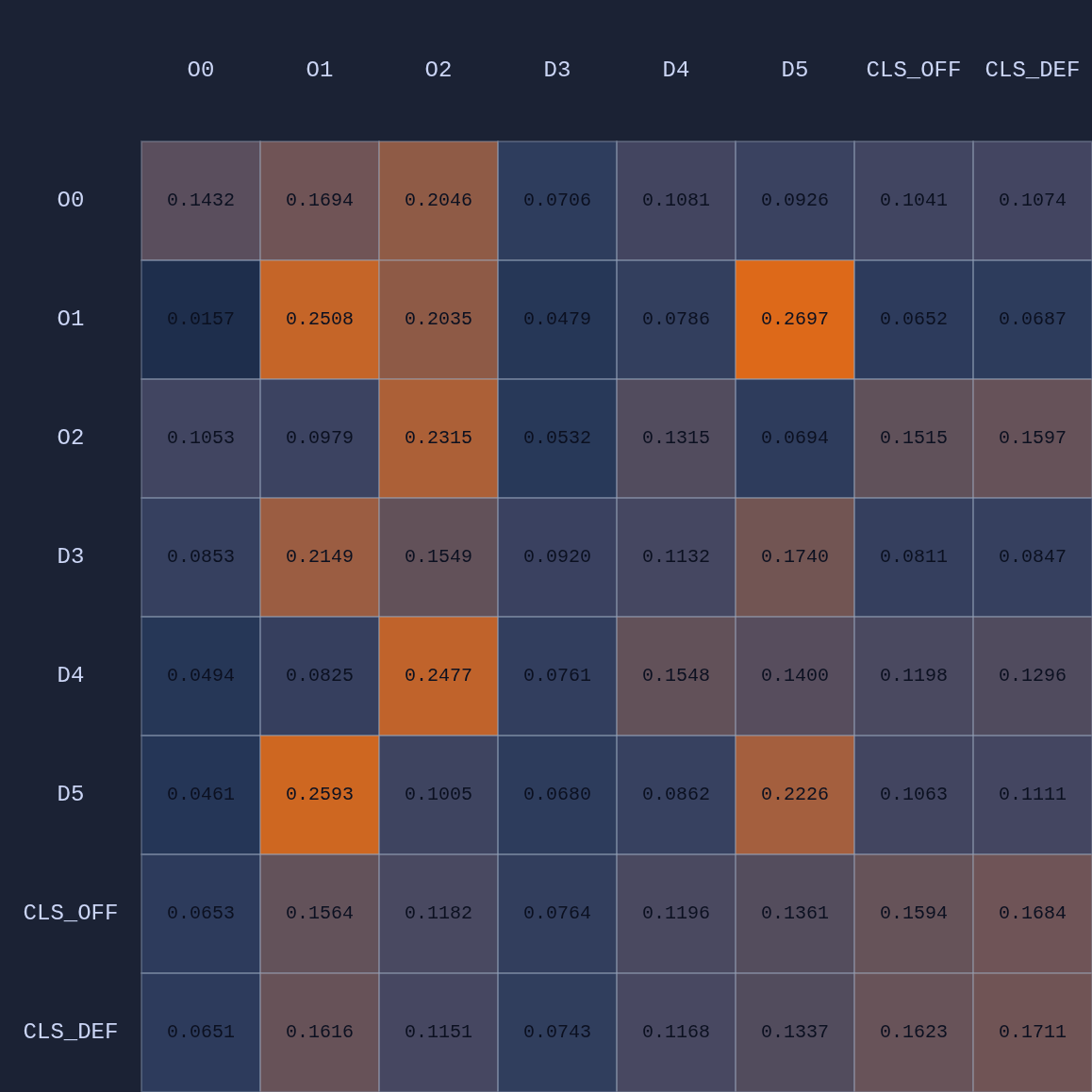

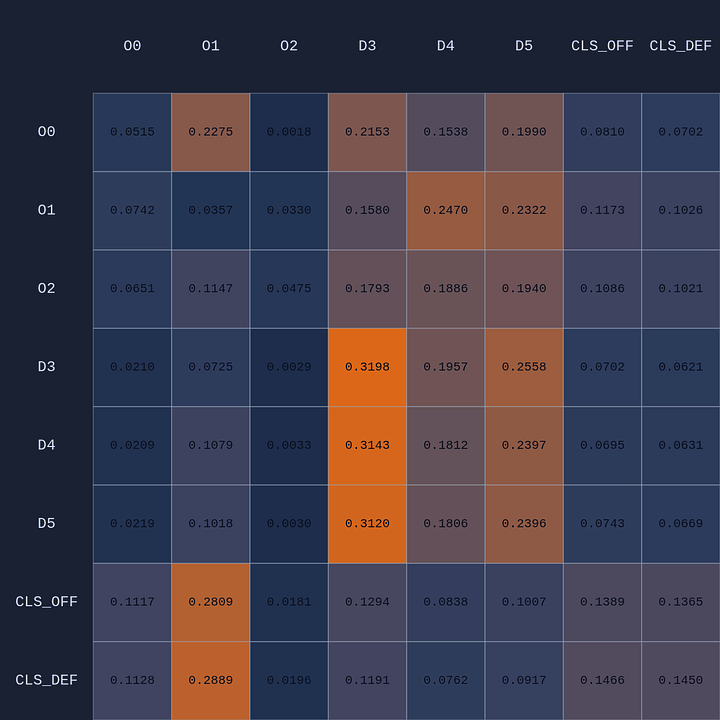

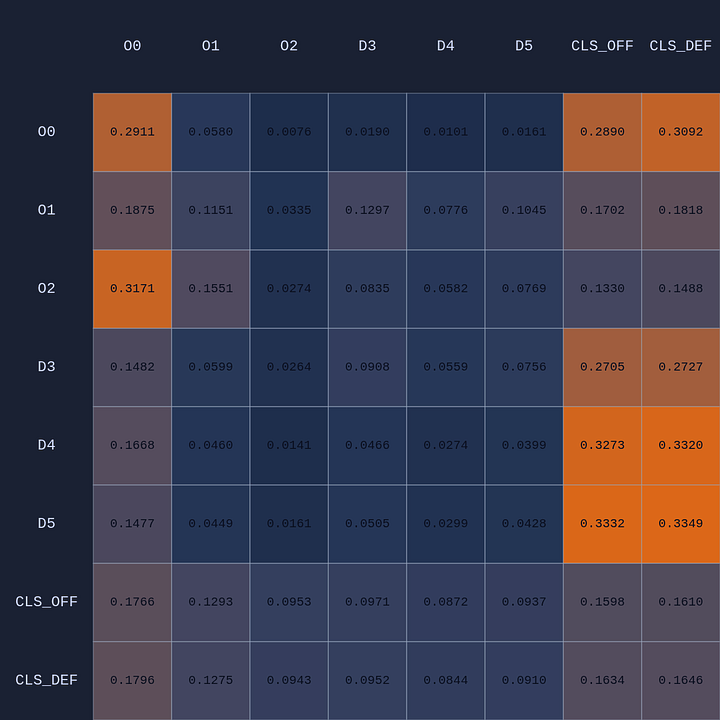

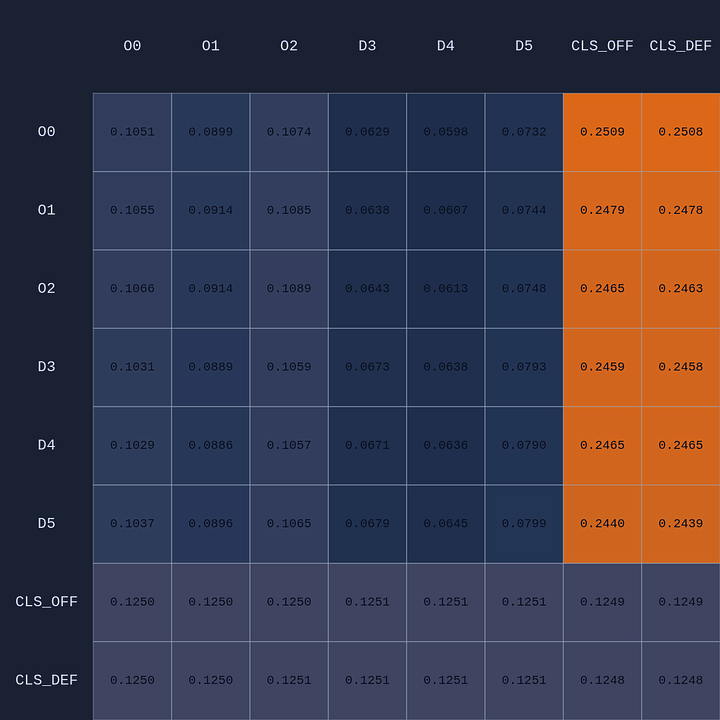

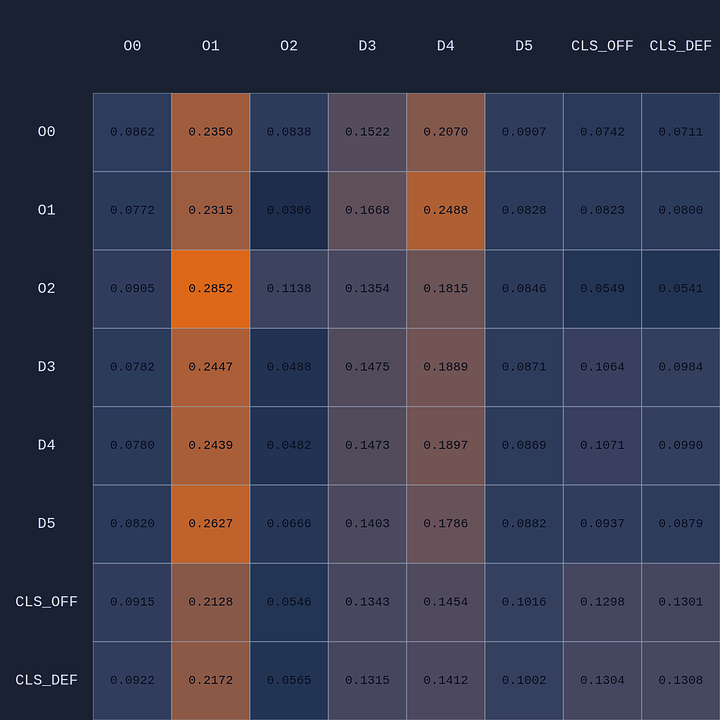

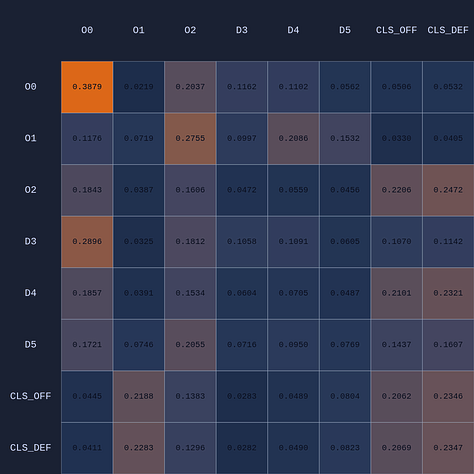

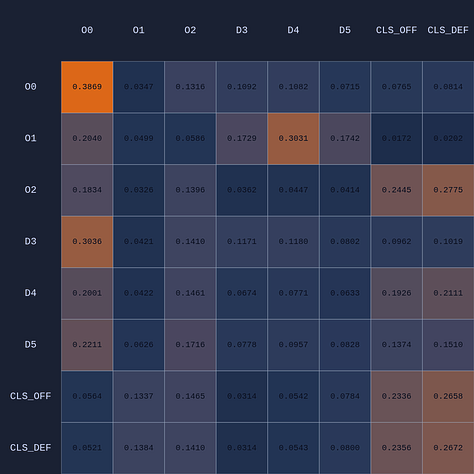

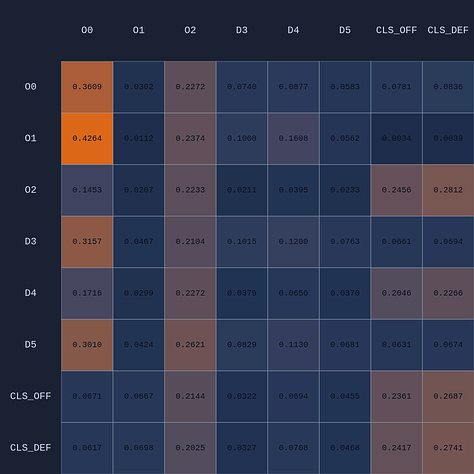

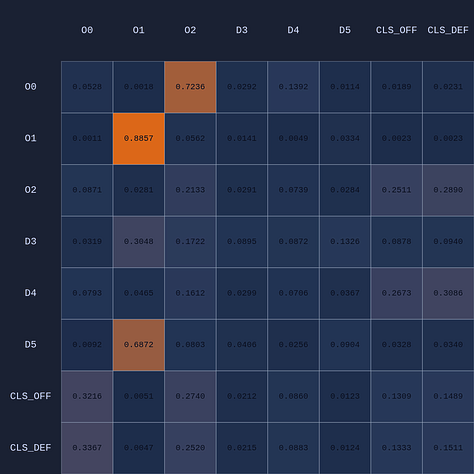

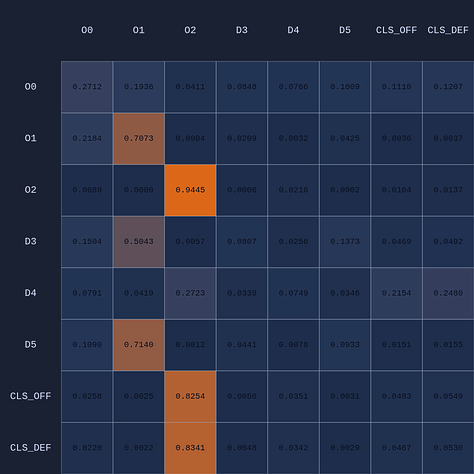

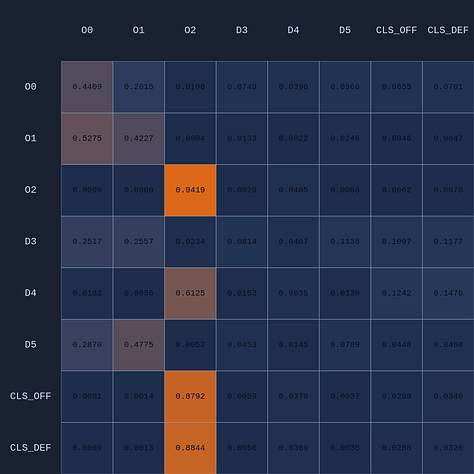

In the table above we’re looking at the average attention across 4 heads. In addition to the player embeddings, there are also two team-level embeddings (CLS). The idea of having multiple attention head is that each one might capture different features or context in the game state, just as in large language models each attention head might capture something different given the context of the sentence with respect to previous context in a paragraph or larger document (or images). Here are the maps for the 4 individual attention heads in this example:

Attention Experiments

Now that we have the lay of the land, let’s see if we can tease out some of what the model is learning through all this attention paying. The easiest way to do this is by manipulating the game state (similar to how we swapped players earlier).

Temporal Policy Evolution

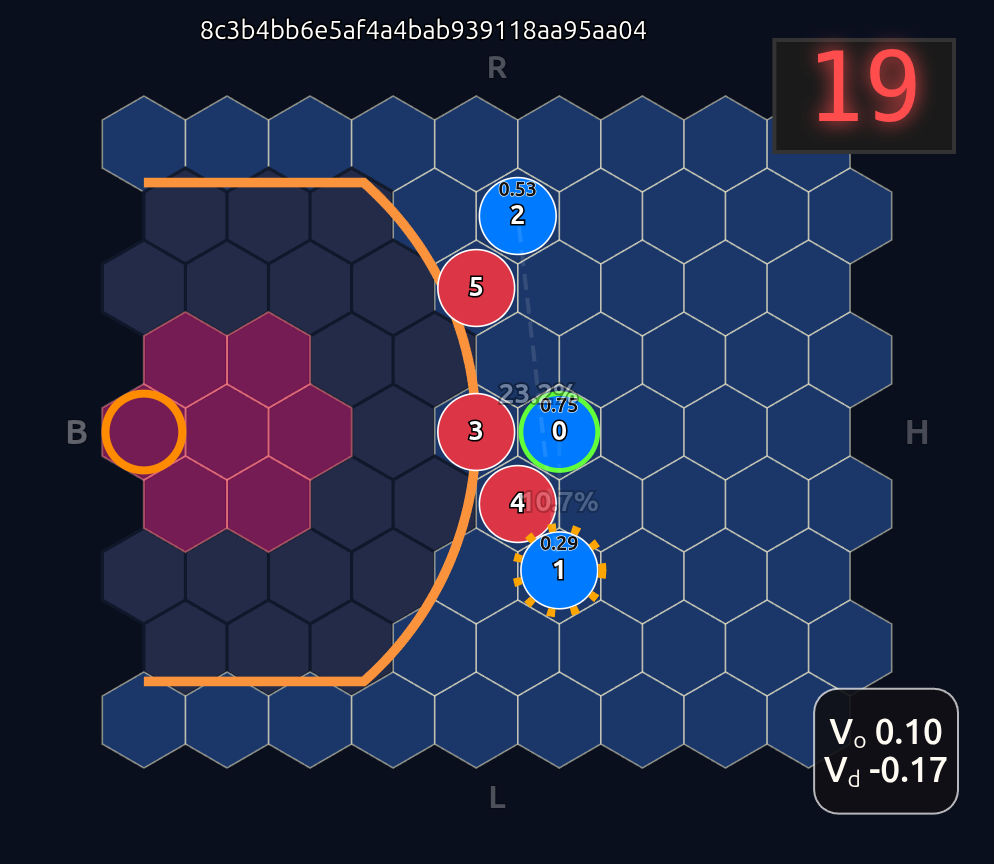

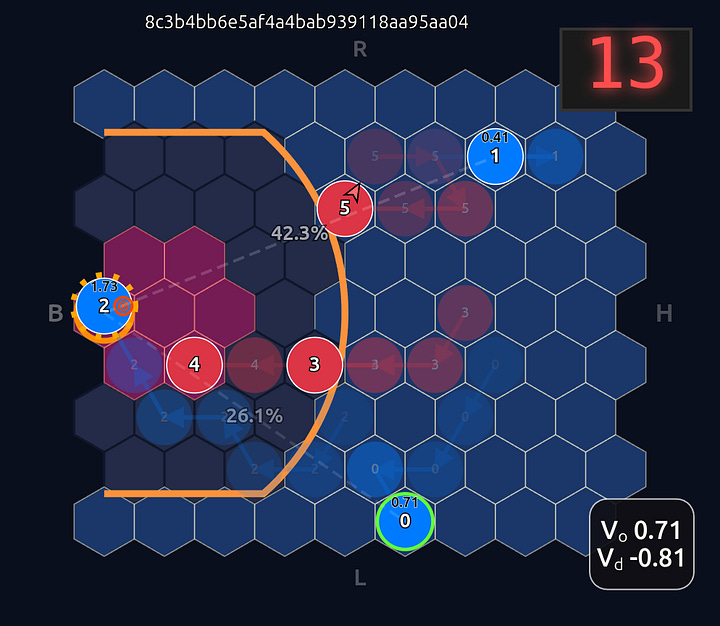

First let’s see what happens for a given state when we swap policies from very early in training to the final learned policy (in this case after ~1B steps over 5 days of training!):

Early in training most of the attention is focused on the ball handler, which isn’t surprising. But you can see by the end of training (lower right) the model is very specific about where it is paying attention. For example, the ball-handler O1 is paying most attention to itself (ie self-attention), and defenders D3 and D4, which makes sense as they are the closest defenders.

Defensive Attention

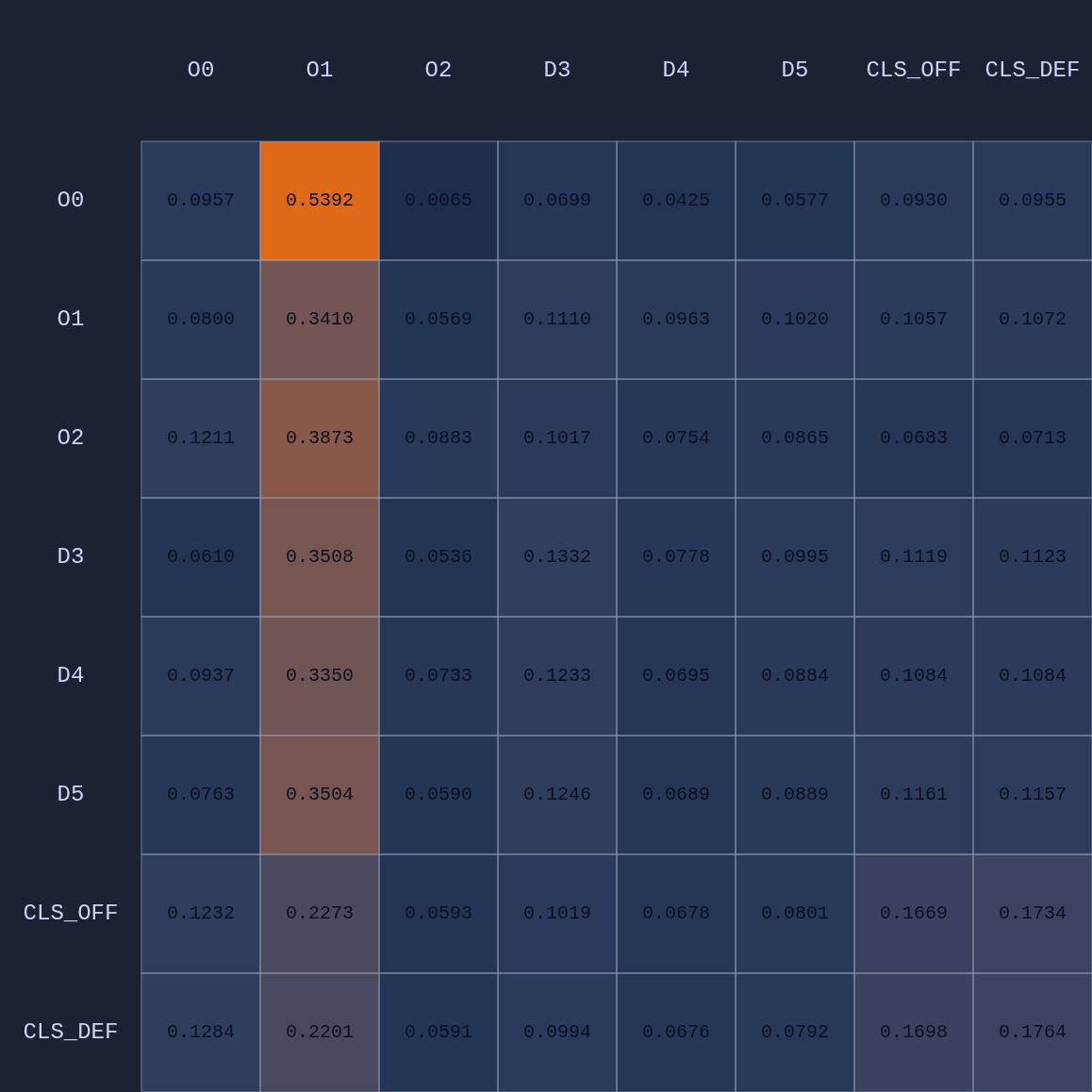

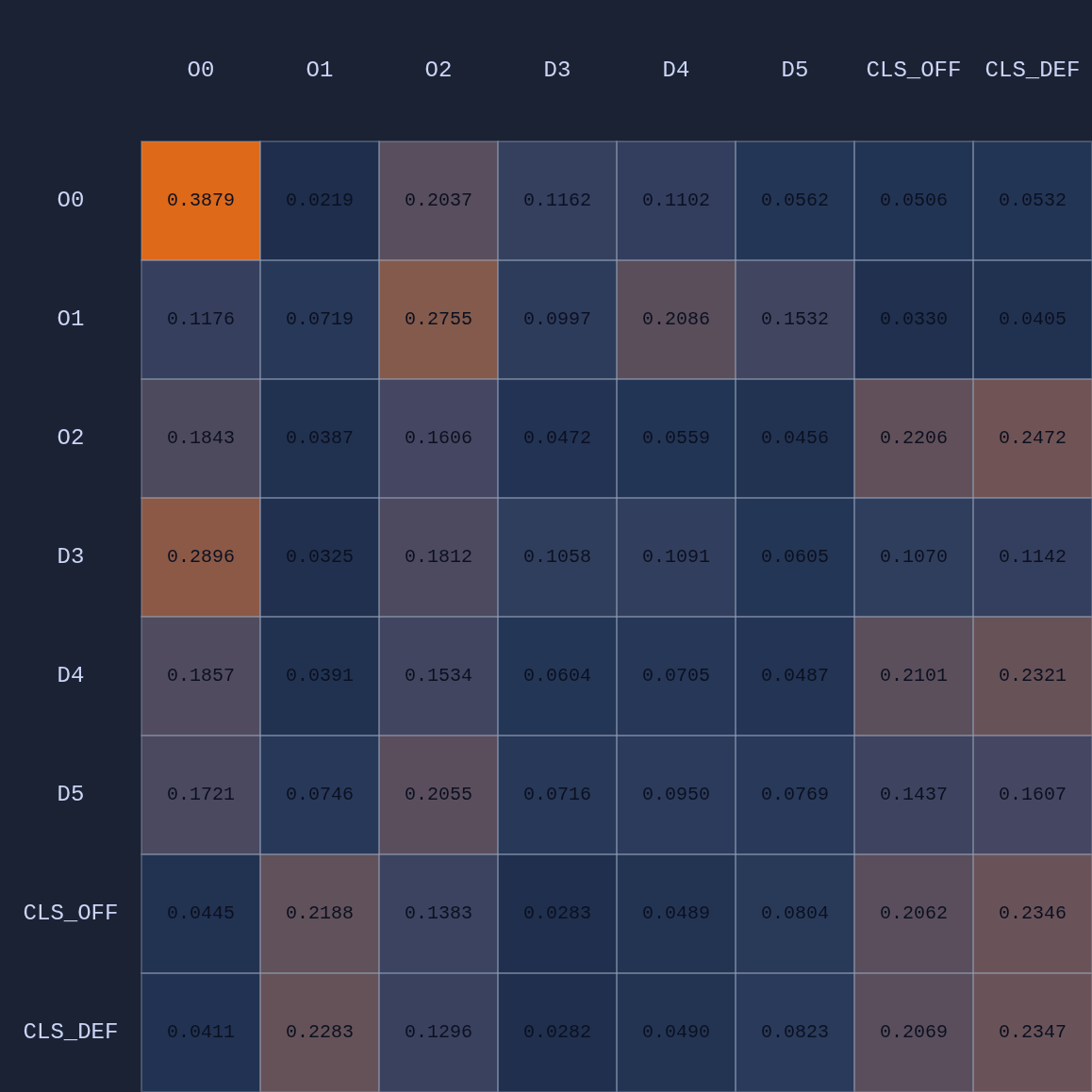

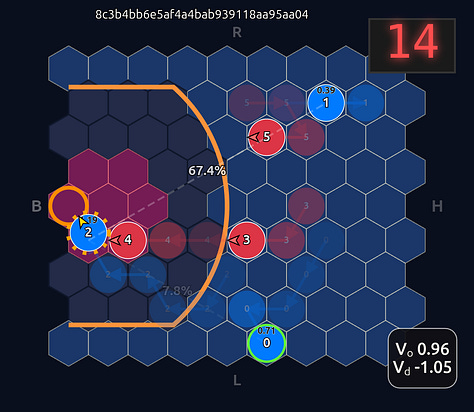

Let’s create a game state that has very clear defensive assignments and see what the average attention map looks like:

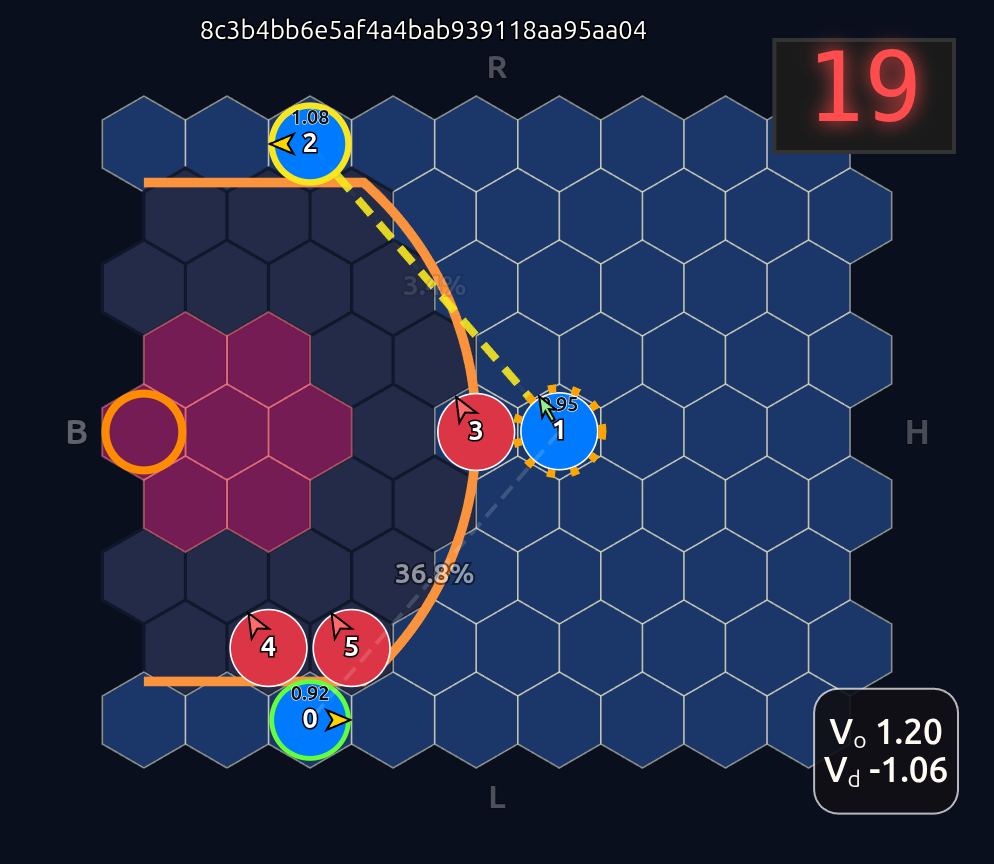

As expected we see that D5 is paying the most attention to O2, D3→O1, and D4→O0. Let’s see what happens if we move D5 over to the other side of the court to double team O0:

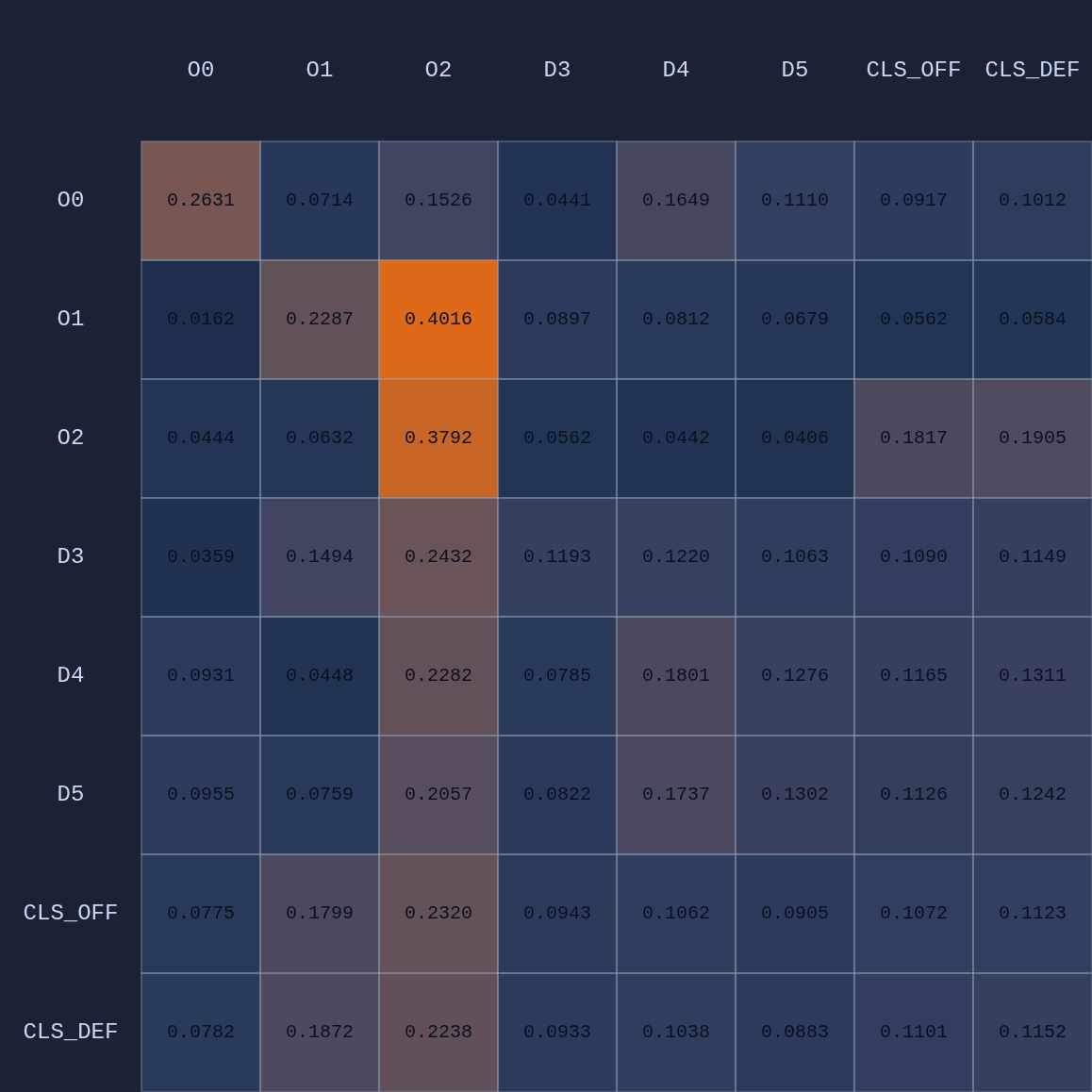

So a couple of cool things have happened. The first and most obvious result of this move is that it opened up O2 for a much more efficient shot (EP=1.08 vs 0.86 previously) and now the highest probability action for O1 is a pass to O2. This policy change is clearly evident in the attention map as we see O1→O2 has suddenly “lit up”. In fact, O1 is now paying more attention to O2 than to itself. Conversely, D5 is now paying relatively more attention to O0 and less to O2 than before, although on average all the defenders are paying high levels of attention to the open shooter compared to their own defensive assignments. There’s something else that’s interesting here…spot it yet? Notice that when D5 moves over to “help” on O0, D4→O1 actually decreases by roughly 50%. Attention is conserved across rows so if more attention is given to one player it must be taken away from some other players!

Individual Head Attention

Let’s take a look at another random game state:

Here is the average attention map for this state:

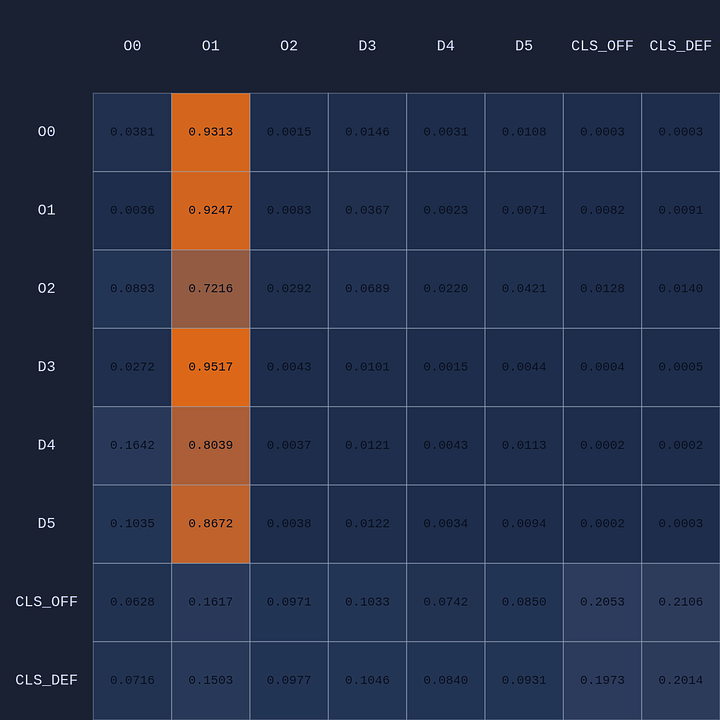

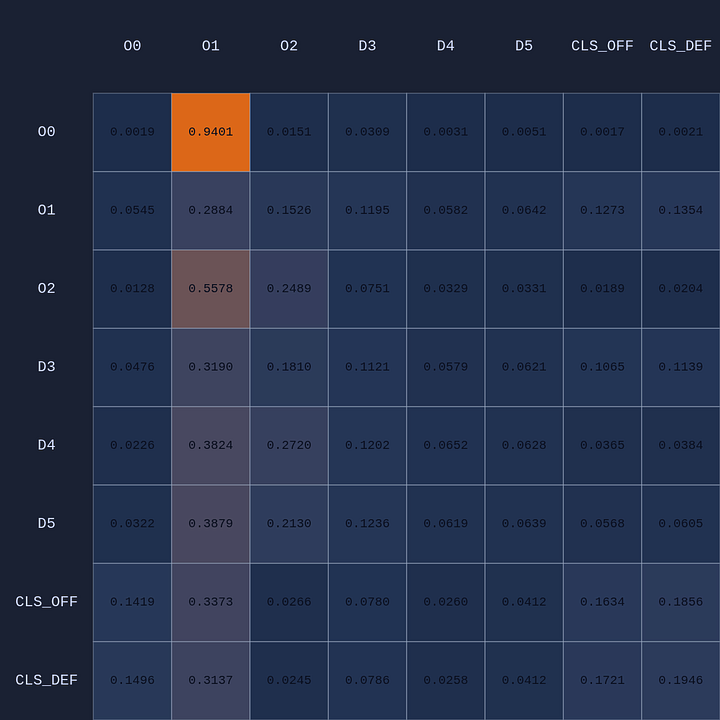

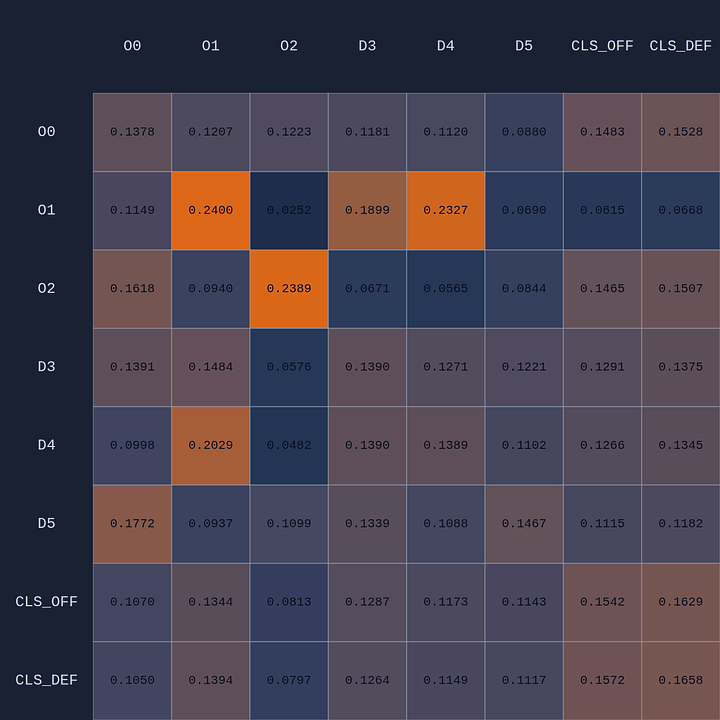

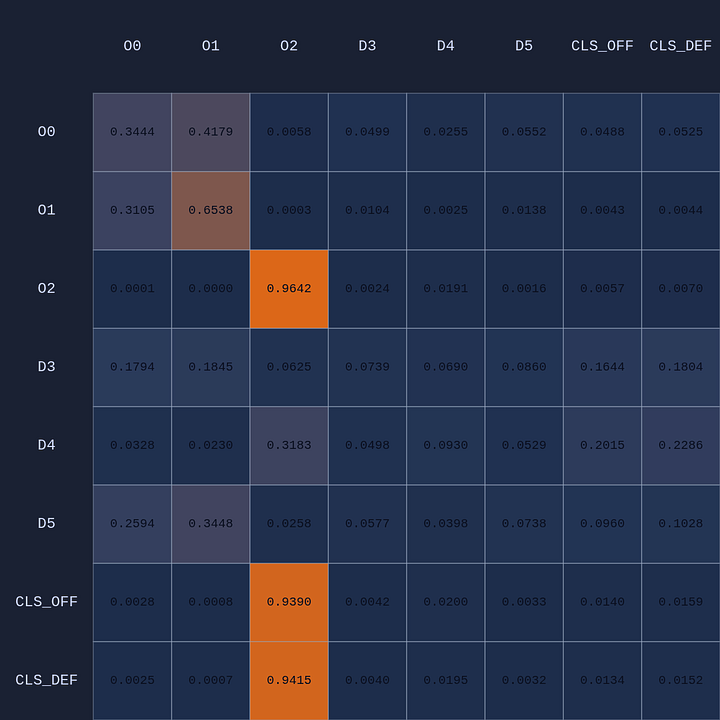

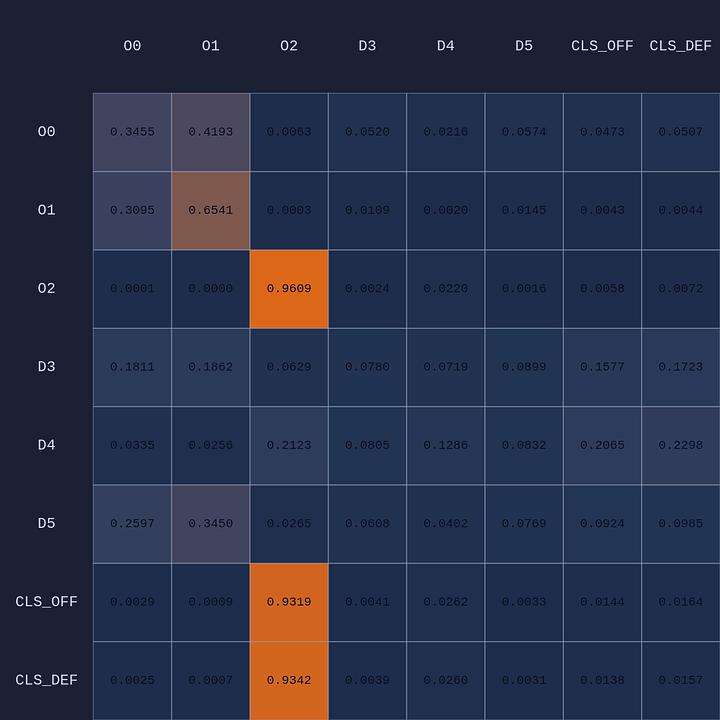

There’s a lot going on there. But if we focus on Attention Head 1 we see something more interesting:

We see that in Head 1 O1 is paying a ton of attention to his teammate O2. Let’s see what happens if I “nudge” O1 to pass by moving the defender D4 one tile away from his original position:

Boom! It looks like Head 1 might be acting as a passing evaluator. Let’s move D4 into the passing lane and see what happens:

Now there’s a very high chance of turning the ball over on a pass to O2 (33.3% TOV%) and the attention diminishes greatly. I decided to play out the rest of this episode to see what would happen.

What you see if you go through each frame is that the attention map for Head 1 lights up the step before a pass is made. In a very real sense you could even say the attention map is telegraphing the pass.

I’m going to stop here as it’s probably enough to digest for now. Hopefully you get the point of all this. Thank you for your attention! Please feel free to leave comments and/or questions or suggestions for future work on this project. Also, if you enjoy BasketWorld, please consider giving it a star on GitHub!